Daidō Moriyama: Provocative Genius or Warhol in a Well?

BY: SAGE PURDON

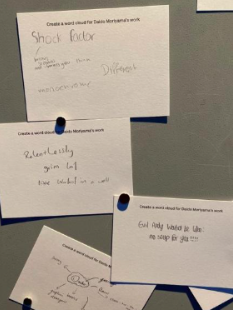

'“Evil Andy Warhol be like: no soup for you!” These were the words I scrawled on a crisp white Post-It note on the wall of the Photographers’ Gallery in London when asked to create a word cloud describing the works of Daidō Moriyama. I had attended the exhibit with a friend whilst on winter break in London, hoping that visiting a plethora of museums and galleries would ease our minds about the coming semester and make us feel a little more optimistic about life – and in retrospect, as we discussed what we had just seen over an oat milk latte and some black and white postcards snaffled from the gift shop for a cheeky 50p each, we decided how wrong we were. It’s certainly true that a Moriyama collection is NOT the kind of event you should pay a visit to when trying to escape from crushing existential nihilism, social anxiety, and doom-scrolling fitness pages on Instagram. However, the exhibition did leave me with a growing sense of curiosity about who Moriyama was, and the reasons for his dystopian mindset, the depths of which to me seemed endless…

For a wee bit of context: Daidō Moriyama is a renowned Japanese photographer known for his raw, high-contrast and often provocative black-and-white street photography. His work has evolved over the years and reflects changes in his personal life, his artistic influences, and the socio-political climate. He is often described as relentlessly bleak due to the dark, raw, and intense nature of his photographic work, and rejected the trend of photorealism popular in Japan in the 1950s, and instead, “sought a revolution in photographic expression” (Masafumi and Fritsch, 2012). In this article, I’d like to explore the chronological evolution of his photography through the lens of both his earlier and later career, specifically through his contributions to Japanese magazines, the Provoke movement and his continued exploration of the bure boke style, a style of photography best defined as “rough, blurred, out-of-focus” and “popularized by Japanese photographers in the late 1960s” (Bohr, 2011).

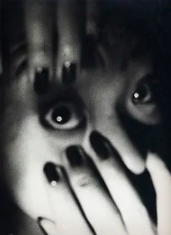

Daidō Moriyama, Untitled, 1990, from the series ‘Letter to Saint-Loup.’

Moriyama began his photographic career working as an assistant to Eikoh Hosoe in the early 1960s. His early works present a viewer with “a dark world, chaotic, consumerist” (Fernández, 2016) and are obviously influenced by the energetic atmosphere of post-war Tokyo. He began to collaborate with various Japanese magazines, capturing the evolving urban landscape and social changes in the country. Moriyama gained notoriety with his participation in the exhibition Japan: A Photo Theatre in 1968. This exhibition featured photographers such as Shomei Tomatsu and Eikoh Hosoe, and it marked a break with traditional photographic styles. This influenced Moriyama’s approach to capturing the complexities of Japanese society.

He also played a crucial role in the Provoke movement, a radical, avant-garde photographic movement that emerged in the late 1960s, which served as “a key turning point in the early careers of these young photographers and in postwar Japanese photography as a whole” (Sas, 2011). This movement sought to break with traditional photographic conventions and adopt a more subjective and experimental style, and presented itself as “a radical magazine, setting out to overthrow modernist photography” (Masafumi and Fritsch, 2012). Moriyama’s contributions to this magazine, including the famous Bure Bure series, showcased his signature bure boke style, characterized by grainy, blurred, high-contrast images. During the 1970s, he faced challenges in the field of photojournalism, and his work often focused on social and political issues, capturing the tumultuous events of the time, which included protests and demonstrations. The stark and raw aesthetic of his photographs during this period reflects his commitment to documenting the harsh realities of Japanese society.

In the 1980s, Moriyama continued to refine and evolve his bure boke style through the lens of “two fundamental concepts: city and darkness” (Fernández, 2016). This period marked a departure from his earlier, more chaotic, and aggressive works. He began to question the direction of his art, which led to a more introspective phase. Moriyama experimented with different subjects but maintained his characteristic grainy, blurred aesthetic. Urban landscapes, street scenes and everyday life remained a constant in his work, and his distinctive style gained international recognition; his works were exhibited in major galleries and museums around the world. Moriyama’s impact on contemporary photography was recognized during this period. Despite his international success, he remained true to his roots, constantly exploring the expressive possibilities of the bure boke. He continued to produce important photobooks, such as Remix and Hawaii, showing his ongoing commitment to pushing the boundaries of photographic expression. The bure boke style persisted, and his later works maintained the stark, abstract, and often provocative elements that defined his earlier career. Moriyama's legacy in photography is marked by his relentless experimentation, his role in shaping the Provoke movement and his contributions to the bure boke style, leaving an indelible mark on the world of contemporary photography and inspiring subsequent generations of photographers to explore new forms of visual expression.

In addition, Moriyama went through an important creative and personal crisis during the 1980s. This period was characterised by a departure from his earlier, more confrontational, and chaotic works, reflecting the changing political climate at the time. This dramatic shift was reflected by events such as “the opening of the World Exposition in Osaka, proudly displaying the successes of Japan’s economy, and events such as Mishima Yukio’s seppuku-suicide” (Masafumi and Fritsch, 2012), which marked a waning of right-wing political heat. (Side note: seppuku, also known as hara-kiri, is truly horrifying. Self-disembowelment is not the way to go, in my opinion.) In the meantime, Moriyama questioned the trajectory of his art and sought new avenues of expression. This crisis led him to delve into introspection and experimentation, challenging himself and the conventions of his earlier work. His exploration during this crisis led him to the core of photographic memory and history, and he began to question the nature of images, memory, and the role of photography in shaping our understanding of the past. Works from this period often featured fragmented and layered compositions, reflecting a sense of temporal dislocation. The images seem to echo the disjointed nature of memory itself, capturing fleeting moments that resist linear narratives.

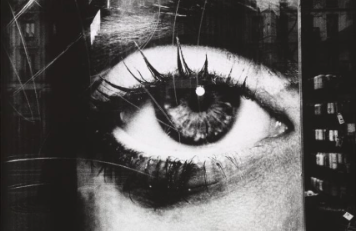

Daidō Moriyama, Eros, 1969, from '‘Provoke 2.’

Moriyama's approach to photography during this period resulted in a disturbing aesthetic. The use of unconventional framing, blurry images, and confusing compositions contributed to the viewer experiencing a sense of visual unease through its “ghostly quality” (Charrier, 2010). The overall effect of his images was intentionally disorienting and triggering, challenging the viewer's perceptual stability and inviting them into a subjective and fragmented visual realm – in the style of a Gaspar Noe film, if you’ve had the fortune/misfortune of experiencing the beauty/ general horror/wacky drug trip of Enter the Void you know. Moriyama pursued multimedia and experimental approaches and integrated video, sound, and installations into his exhibitions. This multidisciplinary approach enhances the immersive and unsettling experience for the audience. By pushing the boundaries of traditional photographic representation, he blurred the boundaries between different art forms and created an environment that was both challenging and captivating. This feeling of mild nausea was intentionally embedded in Moriyama's work, and the physical and emotional reaction was a testament to his success in creating an immersive and powerful experience for the audience. The intentional disorientation served to evoke a deeper engagement with the themes of memory, history, and the subjective nature of perception. His exploration of creative and personal crises, coupled with his deep immersion in photographic memory and troubling aesthetics, left a legacy. His later work challenged the traditional boundaries of photography and expanded its potential as a medium for conveying complex and nuanced narratives. The legacy of this difficult period continued to influence contemporary photographers and strengthened his reputation as an artist who was unafraid to push the boundaries of artistic expression.

Daidō Moriyama, Memory, 2012

However, the thing that struck me most about Moriyama’s work is its bleakness, as his photographs are characterised by high contrast and a deliberately grainy aesthetic. This choice creates a stark visual impact, emphasizing the harsh realities and textures of urban life, and the graininess adds an element of rawness, amplifying the overall sense of desolation in his images. His choice of subject matter contributes significantly to the perception of his work as relentlessly desolate. He often captures scenes of urban decay and marginalised individuals, portraying the darker aspects of society, and reflecting issues such as poverty, crime, and social unrest. Moreover, his approach involves getting close to his subjects, creating an intense and intimate connection with the scenes he captures, particularly in the nude shots from his Provoke series. Although this proximity can be unsettling for us viewers, bringing us face to face with the unfiltered realities of the urban environment, one could argue that rather than presenting these scenes to viewers purely to make them feel ‘uncomfortable’, instead he is trying to embody a “Japanese vision on the theme, which sees beauty in darkness and shadows”, serving as a direct antithesis to the somewhat Warholian culture more familiar to a Western audience “where aesthetics is typically built around light” (Fernández, 2016).

In summary, Daidō Moriyama's creative and personal crisis led him into a period of exploration in which he grappled with the core of photographic memory and history. The resulting works, characterised by an interesting and slightly unsettling aesthetic, induce a sense of vertigo in the viewer, creating a deeply immersive and emotionally charged experience. This period remains an especially crucial chapter in his career and demonstrates his ability to evolve and provoke in the field of contemporary photography. In the words of my friend, “relentlessly grim, lol”. However, while Moriyama's work may be perceived as bleak, to me, it also possesses a certain beauty and authenticity. His photographs reflect the complexities of urban life, and his tireless exploration of these themes has had a significant impact on the world of photography, challenging us to confront the harsh realities of the human experience.

Some thoughts on Moriyama written on the wall at the Photographers’ Gallery.

Friend Mahalia perusing copies of Hawaii and Remix (Moriyama’s photobooks) at the exhibit, Photographers’ Gallery.

ST.ART Magazine does not own the rights to any image used in this article

Bibliography:

Bohr, M., 2011. Are-Bure-Boke: Distortions in Late 1960s Japanese Cinema and Photography. Dandelion: Postgraduate Arts Journal and Research Network, 2(2).

Charrier, P., 2010. The Making of a Hunter: Moriyama Daidō 1966–1972. History of Photography, 34(3), pp.268-290.

Fernández, J.M.G.C., 2016. The concept of centre-periphery in the work of Daido Moriyama. SAUC-Street Art and Urban Creativity, 2(1), pp.19-26.

Masafumi, F. and Fritsch, L., 2012. Is the World Beautiful? Moriyama Daidō’s Provocation of the History of Photography. Art in Translation, 4(4), pp.459-473.

Sas, M., 2011. The Provoke Era: New Languages of Japanese Photography. In Experimental Arts in Postwar Japan (pp. 180-200). Harvard University Asia Center.