'Don't stop, thinking about tomorrow': Fleetwood Mac's 'Rumors' at 45

By Eleanor Grant

In October 2020, something strange happened. More than forty years old, a song found its way back to the top of the charts thanks to a fairly random viral video of a man skateboarding down a street, sipping from a bottle of Cran-Raspberry Ocean Spray. The song playing in the background of said video was ‘Dreams’ by Fleetwood Mac, one of the lead singles to come from their 1977 album Rumours, arguably the band’s most cohesive and famous body of work. The way this video, and countless parodies of it, took off is undeniably a testament to the feel-good, easy listening sound the brief snippet of the song encapsulates. What these videos do not reveal, however, is the complicated history behind Rumours and the fraught layers of anger, loss and resentment that make up the bulk of its lyricism. 45 years on, Rumours remains one of the best-selling albums of all time, having sold 40 million records at the time of writing, and continues to resonate with listeners on a mass scale in a way that very few albums have.

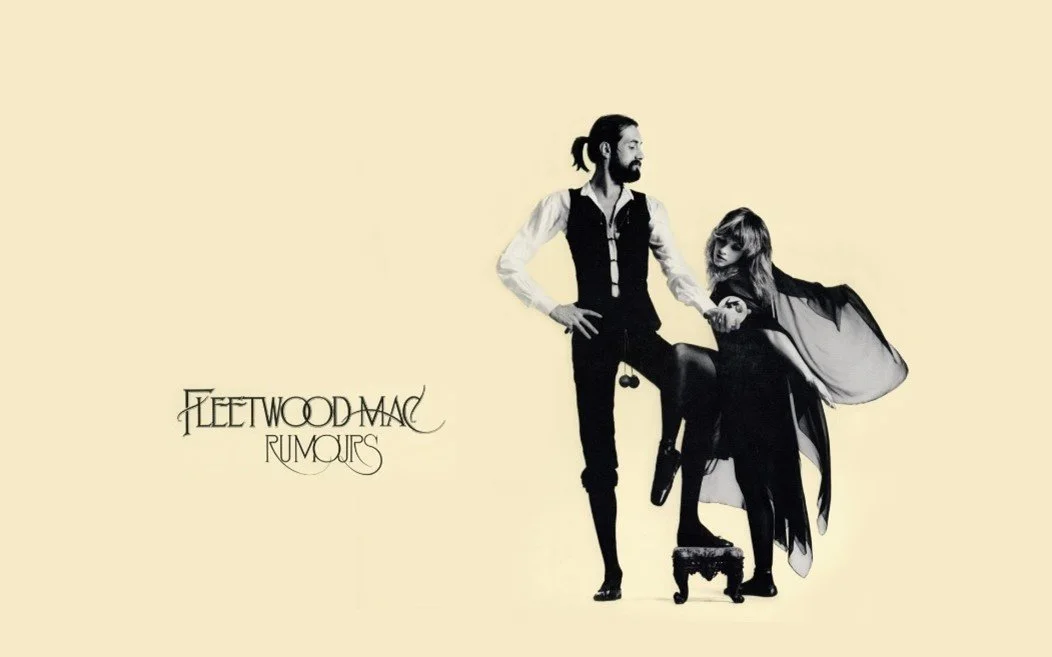

When Fleetwood Mac came together to write Rumours, the group was at odds with one another. Each member was dealing with an ending of sorts – Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham’s tumultuous relationship was coming to an end, Christine and John McVie were in the midst of divorce proceedings, and Mick Fleetwood was struggling with the recent discovery of his wife’s infidelity. Rumours was Fleetwood Mac’s eleventh studio album, but the first to involve writing credits from Nicks, Buckingham, the McVie’s and Fleetwood. The result, musically, was vitriolic. Their personal blows, combined with heavy substance abuse, created a cocktail of contempt that would form the groundwork for Rumours and much of their follow-up albums.

The album begins with ‘Second Hand News’, whose opening lyrics define Rumours as the break-up record it is (‘I know there's nothing to say/Someone has taken my place’). Buckingham’s ode to Nicks, and the women he encountered after the end of their relationship, the song is anything but downcast or downhearted. His mix of folk influences and heavy scat usage in the chorus (‘Bow-bow-bow-bow-buh-buh-bow’) allow him to convey the sense of euphoria in no longer being with Nicks. As Jessica Hopper puts it, the sound is ‘upbeat but totally fuck-you’. There is a suggestion though, in earlier verses, that Buckingham’s feelings towards Nicks, and about himself, are much more complex than the cheery instrumentals may suggest (‘I know I got nothing on you/I know there's nothing to do’). ‘Go Your Own Way’, another of Buckingham’s works, is by far the most angst-ridden song on the album, steering Fleetwood Mac away from the soft rock sound it had long been associated with. Led by searing, heavy guitar parts and stomping drums and bass, it is a furious encapsulation of everything you might want to say to an old flame, knowing there is nothing you can do to stop the relationship from burning up. It carries over the same sense of freedom from ‘Second Hand News’, but the claims he makes are stinging and, according to Nicks, unfounded. ‘Tell me why everything turned around/Packing up, shacking up's all you wanna do’ is perhaps the angriest turn of phrase Buckingham includes, and one which has infuriated Nicks, forced them to sing backup on the song, for decades. ‘Every time those words would come out onstage,’ she said, ‘I wanted to go over and kill him’. There is no denying the ongoing, never-ending fallout of their relationship, one which has marked performances of the song for decades and, in many ways, defined the story of Fleetwood Mac. A band not unaccustomed to psychodrama, the conflict became intrinsic to the creative process and ‘Go Your Own Way’ is the most celebrated example of it.

Still, Nicks was able to stick a knife or two of her own in writing ‘Dreams’, which remains Fleetwood Mac’s only hit to ever reach No.1 on the US charts. Deceptively smooth in typical Nicks fashion, it calls on Buckingham to remember ‘What you had/And what you lost’ while the heartbeat which ‘drives you mad’ like something out of Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘Tell-Tale Heart’ is a reminder of the loneliness that comes from so-called ‘freedom’, rather than the elation that Buckingham fixates on. However, it is ‘Silver Springs’, originally a B-side to ‘Go Your Own Way’ which eventually made it to the remastered Rumours after much dispute, that reveals Nicks’ sorrow over what could have been. In response to Buckingham’s red-faced, guitar-smashing anger, Nicks offers a painful portrait of disappointment in the relationship, which she laments could have been her idyllic sounding ‘silver spring’. While each calls on the other to entertain the notion of other people, it is telling that both Buckingham and Nicks’ songs turn on the mention of said other people. ‘I'll follow you down 'til the sound of my voice will haunt you’ she vows, ‘You'll never get away from the sound of the woman that loves you’. Performances of ‘Silver Springs’, with Buckingham singing backing vocals and refusing to break eye contact with Nicks, are notoriously intense and have become something of legend. Very few performers can say they have made an ex-lover affirm words as damning as ‘Time cast a spell on you but you won't forget me’, but Nicks is one of them.

The McVie’s contributions to the album were less poisonous, but equally as affecting. Christine’s ‘Songbird’ is a devastatingly simple piano ballad addressed to a detached lover, most likely John, whose disregard for her only encourages her to love him like ‘never before’. Though her relationship is seemingly hopeless and like a songbird, she already ‘knows the score’, her affection does not wane. ‘Oh Daddy’ walks on similar ground to ‘Songbird’ but is far more desperate in its need for approval. Broken up by dark organ chords and simmering percussion, McVie sounds almost ashamed of what she admits to – namely, being emotionally dependant on another person for her feelings of self-worth. She speaks of feeling unequal, and even unworthy, of her partner even though their relationship has become a source of pain (‘Oh, Daddy, you know you make me cry/How can you love me, I don't understand why’). Ironically, in reverse of her earlier confessional narratives, Christine is also the writer behind ‘Don’t Stop’, the album’s most optimistic take on the breakdown of a relationship. Written as a duet with Buckingham, it is an address to John in the aftermath of their divorce, who she encourages to ‘think about times to come/And not about the things that you've done’, rather than seethe and wallow in true Buckingham-Nicks style. There is no denying, on the part of Christine, that their relationship has not been fractured (‘I know you don't believe that it's true/I never meant any harm to you’) but it is one she is willing to work on in time (‘All I want is to see you smile/If it takes just a little while’). Christine’s writing allows Rumours to go beyond simply expressing anger at the past, and considers the future as well, evident in the rousing, foot-stomping chorus of ‘Don’t Stop’ which became the mantra for Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign.

However, it is ‘The Chain’, a collaborative effort with writing credits from all five members, which is perhaps the most symbolic of Rumours as a whole. For a band that has seen multiple walk-outs from nearly every single member, there is a deep irony in writing an anthem about the bond between the group, one which they imply is unbreakable (‘I can still hear you saying/You would never break the chain’). The infamous bass solo, following a lull in the post-chorus, is almost a metaphor in and of itself, representing the release of resentment that has built up over the course of the song and the writing of the album. Though their relationships have been tried and tested, the McVies, Fleetwood, Buckingham and Nicks all agree that for better or for worse, ‘The Chain’ will ‘keep us together’ whether they are on speaking terms or not. With a foot in the door of the past and another in what is to come, Rumours has earned its status as a genuinely timeless album. Dark, complicated and deeply human, 45 years on, as McVie wrote, it has only come to be ‘better than before’.

ST. ART Magazine does not own the rights to any pictures used in this article.