Architectural Time Capsules: Exploring Warsaw's Rich history through 10 buildings

by Nina Zmelonek Mulligan

For the initial two decades of my life, my sense of identity has been closely intertwined with the city I call home. Yet, as is often the case, familiarity can breed a degree of complacency, and I found myself taking the architectural landscape that surrounded me on a daily basis for granted. I decided to adopt a more discerning perspective by closely examining ten prominent structures within the city. Whether meticulously restored or still existing in their original design, these buildings offer a compelling lens through which to explore Warsaw's historical narrative against the broader history of Poland. They provide valuable insights into the city's evolution across diverse architectural styles. While not an exhaustive survey, this curated selection brings to light notable structures that encapsulate Warsaw's architectural journey and its historical moments.

The Barbican, Warsaw

1.The Barbican

Initially built in 1548 as part of the defensive fortifications of the Old Town, this three-level semicircular brick bastion atop the moat was conceived by the Venetian architect John Baptist. Its origins trace back to a period when the last two kings of the Jagiellonian dynasty welcomed Northern Italian builders to Mazovia, leading to a fusion of local Gothic styles with Italian Renaissance influences, evident in various church constructions across the region. The Barbican was built around 20 years after Sigismund I the Old incorporated the Duchy of Mazovia into the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. Despite its construction, the Barbican's defensive utility became obsolete due to advancements in artillery, and it notably engaged in defensive actions just once, during the Swedish Deluge when King Jan Kazimierz's forces retook it from Swedish control in 1656. A reconstruction supervised by Wacław Podlewski between 1952 and 1954 aimed to restore the Barbican based on 17th-century engravings. Today, this historic landmark serves as a passage connecting the Old Town and the New Town just as it did almost 500 years ago.

Sigismund's Column, Warsaw

2. Sigismund's Column

Erected in 1644, the Sigismund's Column stands as an emblem of historical significance, being the oldest secular monument in Warsaw and the initial column built in early modern Europe to honor a secular figure. Sigismund III Vasa's ascension to the throne in 1587, challenged by Maximilian III of Austria, was solidified following his triumph in 1588 thanks to Jan Zamoyski. His rule marked the end of Poland's Golden Age and coincided with the zenith of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, established in 1569, uniting both realms under a common monarch. As Warsaw burgeoned rapidly toward the end of the 16th century, it transitioned from a mere electoral site to becoming the capital city in 1596, following King Sigismund III Vasa's decision to relocate it from Kraków. The column, a tribute raised in his memory by his son Władysław IV Vasa, now stands as an entry point to the Old Town and marks a centre point for the enormous square in front of the Castle. Designed by Augustyn Locci and Constantino Tencalli, this monument not only memorializes a significant monarch but also symbolizes the pivotal historical transition and architectural legacy within Warsaw's urban landscape. Now it serves as a landmark and the big square has been an important place for people to gather for celebration but also protests such as the All-Poland Women's Strike in 2016 that emerged in opposition of the tightening of abortion laws.

Palace on the Isle, Warsaw

3. Palace on the Isle

The Palace on the Isle embodies a pivotal historical narrative within Warsaw. Originally a Baroque bathhouse pavilion, it underwent extensive reconstruction from 1772 to 1793 in the classical style, under the design of Dominik Merlini and Jan Chrystian Kamsetzer. ommissioned by King Stanisław August Poniatowski, the palace served as the monarch's summer retreat and a vibrant centre for cultural and intellectual discourse, notably hosting the esteemed Thursday Dinners. These gatherings epitomized the Enlightenment era in Warsaw, bringing together luminaries from diverse fields, creating a space for discussions and interactions, mirroring French salons. Reflecting the King's personal taste, the Palace's interior and exterior exude a distinctive style, known as the Stanisławian style, uniquely blending classical and Baroque elements. This stimulating period, marked by cultural and intellectual fervour, came to a sobering end with the Third Partition of Poland in 1795 (enforced by Russia, Prussia and Austria), relinquishing the nation's sovereignty until 1918. The Palace on the Isle remains not just a physical structure but a symbol of a bygone era, encapsulating the cultural and intellectual zenith of the Enlightenment within Warsaw's historical fabric.

Hala Targowa Koszyki, Warsaw.

4. Hala Targowa Koszyki

The Koszyki Hall, an emblematic heritage shopping arcade in Warsaw, was established in an Art Nouveau architectural style at the turn of the 20th century. Reflecting the city's need for an enclosed market hall due to its rapid expansion and sanitary issues at open air markets, this iconic structure embodied modernity and sophistication. The exterior design boasted ornate sculptures and intricately carved cartouches featuring the mermaid, a symbol synonymous with Warsaw, alongside motifs inspired by animals and food. This architectural masterpiece provided designated spaces for diverse trades, catering to the specific needs of each. Butchers had marble tabletops for their craft, fishmongers were equipped with pools, and grocers had access to cold rooms and coolers. The Koszyki Hall's design emphasized not just functionality but also a sense of aesthetic beauty and modern convenience, contributing significantly to the city's architectural heritage and reflecting the evolving needs of the bustling city at the time. With the two side wings and the northern wall of the arcade still intact the Koszyki Hall was restored in 2016 and can be visited with many restaurants, bars and stores on offer.

PAST Building, Warsaw

5. PAST Building

At the outset of the 20th century, the ascent of reinforced concrete transformed architectural possibilities, enabling the construction of taller structures and the integration of larger glass surfaces. Among the seminal works of early Polish modernism before 1914 stands the PAST building, erected between 1904 and 1910. Initially accommodating the Swedish-owned company Towarzystwo Akcyjne Telefonów, known as Cedergren, it later came under the ownership of the PAST company. Situated in the centre of Warsaw on Zielna Street, this building soared to a height of 51.5 meters, making it the tallest on the continent at the time. With a design reminiscent of a medieval castle tower, the structure blends elements of modernism with new historicism, drawing inspiration from Romanesque and Gothic forms. During World War II, the building held significant importance, becoming a battleground for the Polish Underground during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Attesting to its historical significance, the emblem of the Polish Underground State and the Home Army, the Kotwica (Anchor), is prominently placed atop the building, emphasizing its enduring legacy within Warsaw's architectural and wartime history.

Prudential House, Warsaw

6. Prudential House

The Prudential House, constructed between 1931 and 1933 during the interwar period in the Art Deco style, stood as a pinnacle of modernity in Warsaw. Functioning as the headquarters for the British Prudential Insurance Company, this landmark building soared as the tallest structure in the city, an impressive eighteen-story skyscraper standing at 66 meters, ranking as the sixth tallest in Europe. Designed by Marcin Weinfeld, it encompassed office spaces on the lower levels and opulent apartments higher up, embodying a forward-thinking architectural approach. Notably, the innovative steel framework was the brainchild of Stefan Bryła and Wenczesław Poniż. Embellished with sculpted allegories representing industry and trade by Ryszard Moszkowski, along with the installation of elevators and a television antenna in 1936, the Prudential House became an emblem of a burgeoning Warsaw, symbolizing both national and international design elements. The building fell victim to the destruction of the Second World War. Nevertheless, the Prudential House has been resurrected in its original modernist style and currently hosts the five-star Warsaw Hotel.

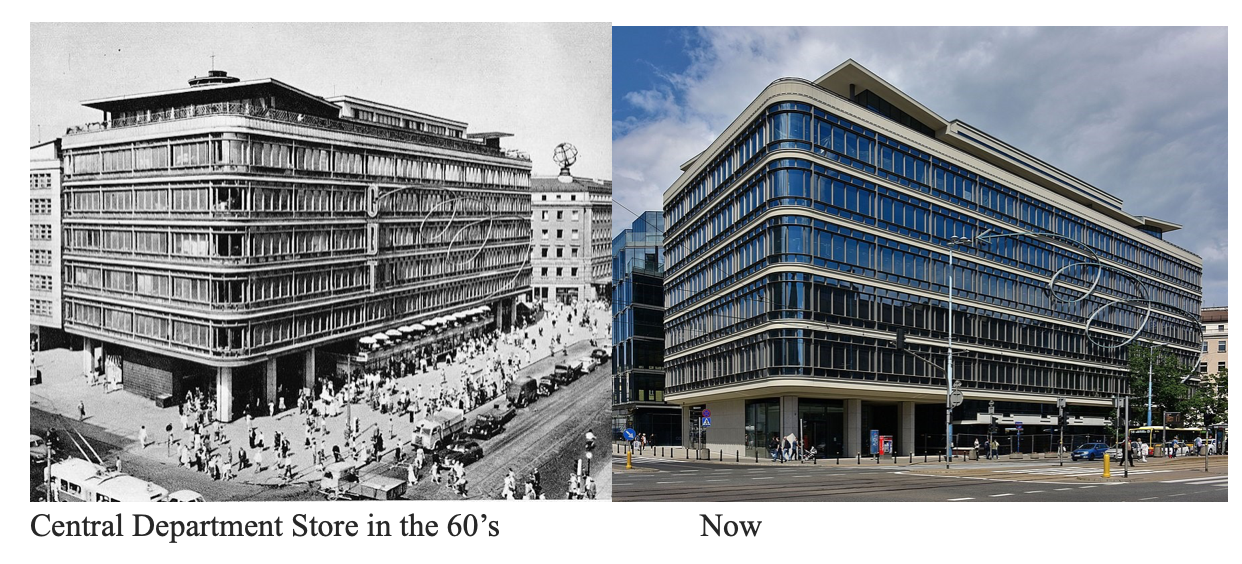

Centralny Dom Towarowy - Central Department Store, Warsaw

7. Centralny Dom Towarowy - Central Department Store

The Second World War left Warsaw in ruins. Over eighty percent of the city was destroyed. What followed in the late 40s was a period of intense planning with the creation of designs for the rebuild of Warsaw. The Centralny Dom Towarowy (Central Department Store) was designed in 1947–1948 by Zbigniew Ihnatowicz oraz Jerzy Romański. It was like a lighthouse in the sea of ruins. It was not favoured by the communist authorities because of how it symbolized capitalist ideas and modernity, but it was adored by Warsaw residents. It was one of the designs that escaped the rigour of social realism doctrine which was officially declared the stately style between 1949-1954 and was build according to original the plans.

The Palace of Culture and Science, Warsaw

8. The Palace of Culture and Science

Social realism, a style shaped by the Communist bloc, extended its influence from literature and art to architecture. It called for art to embody realism in form while conveying socialist content, aligning with the tenets of Marxism and Leninism to promote the party's principles. Introduced in Poland in 1949 after discussions among party architects in Warsaw, this architectural approach firmly rejected Western design trends, emphasizing that architecture should not prioritize aesthetics but should instead express the strength and authority of the state. A prominent exemplar of Social Realist architecture in Warsaw is the Palace of Culture and Science, completed in 1955, designed by Soviet-Russian architect Lev Rudnev in The Seven Sisters style, a group of Stalinist skyscrapers in Moscow. An agreement between the Polish People's Republic and the Soviet Union in 1952 led to the construction of this imposing tower, albeit seen as an imposed and unwelcome "gift" to Poland. It was erected with grand propagandist celebrations and initially bore the name of Joseph Stalin upon its completion. Today, the Palace continues to house various public and cultural institutions, including theaters, cinemas, libraries, and university faculties, serving as a vibrant cultural centre in the city.

The Eastern Wall of Marszałkowska Street , Warsaw

9. The Eastern Wall of Marszałkowska Street

Located near the Palace of Culture is the The Eastern Wall of Marszałkowska Street. It is an urban-architectural complex composed of three skyscrapers, four lower buildings to the east of them and four department store buildings (Wars, Sawa, Junior and Sezam) that come out onto Marszałkowska Street. Behind the complex there was a cinema and theatre separated from the department stores by a passageway strictly for pedestrians. The enormous terrain of rubble, left after the destruction of buildings and tenement houses in the Second World War had to be filled. The architectural competition was won by Zbigniew Karpiński and his design was bult between 1962-1969. The complex is one of the most outstanding achievements of modernism in Poland.

Interior of the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw

Exteriors of the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw

10. Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews

Located on the grounds of the former Warsaw Ghetto, the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews opened in 2014. Prior to the Second World War, Warsaw was home to nearly 370,000 Jews, comprising just under 30 percent of the city's population. The museum, situated facing the memorial honouring the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, symbolizes the historical struggles and resilience of the Jewish community in Poland. Designed by Finnish architects Rainer Mahlamäki and Ilmari Lahdelma, the building's name, "Polin," carries a dual meaning in Hebrew, signifying either "Poland" or "'here you shall rest," relating to a legend about the first Jews arriving in Poland. The museum's striking central feature is the cavernous entrance hall, the undulating, separated walls of which represent the fractured history of Polish Jews. Resembling a gorge, it also alludes to the biblical crossing of the Red Sea in the Exodus. The museum's main exhibition, housed on the lowest level, meticulously chronicles the comprehensive history of Jews in Poland, spanning from the Middle Ages to contemporary times, encapsulating their experiences, culture, and contributions amid historical turbulence, including the tragic events of the Holocaust and the events of 1968, which forced thousands of Jews to emigrate. The Polin Museum stands as a powerful testament to the enduring spirit and rich heritage of the Jewish community in Poland, encapsulating its complex history within the architectural tapestry of Warsaw.