Petticoats, Crinolines, and the Carnivorous Pitcher Plant

By Hannah Ruskin-Dodd

An account of Marianne North’s travels through Sarawak, Borneo, this piece dissects the work of North through a cultural and societal lens as a solo female explorer, scientist, and artist. Whilst she has sculpted the field of botanical science and typography - a rather impressive feat for a woman of the time - her contributions have aided the spread of imperialist ideology, casting a shadow over the British Empire to this day.

Deep in the primaeval jungles of Sarawak, the rich flora local to the region of Kuching thrives, attracting scientists, scholars, and artists for decades. As far back as the 1850s, Russell Wallace, a famous British naturalist and explorer, stayed to collect biological specimens to document and preserve back in Europe with the help of his *Malay guide.

The rich biodiversity soon drew Victorian botanical artist Marianne North (shown left, c. 1886). North, born in 1830, was a somewhat eccentric character, equipped with colourful paints and few accessories, travelling to the tropics, and documenting exotic plants yet to be illustrated in European literature. Leading a controversial lifestyle for a woman of her time, her art was not immune to similar judgment. Yet, with her more abstract depictions of botanical specimens, refusing to conform to the traditional codes of scientific typography, North blended the conventional sense of science and art. It brings into question, how did a woman with a background shrouded in tradition and strict expectations manage to break through the glass ceiling and reshape the future of botanical art? The answer may lie in the ever-prominent class divide, perpetuating Victorian society more than traditional gender roles. As the daughter of a respected parliamentarian, Frederick North, she was well-versed in art and music at a young age. Still, with the means and wealth to travel, her appetite for adventure grew.

As she would recall a lifetime later, she fell under the spell of the exotic red Amherstia nobilis — “one of the grandest flowers in existence,” which made her “long to see the tropics.” Having obeyed the siren song of that yearning, for the next three decades, she stubbornly resisted the central conventions of her era. Her travels saw her face storms, snakes, typhus, broken bones, scorching desert heat, long stretches of dirty drinking water and the death of her father, all the while immortalising nearly a thousand plants, most of which botanists had never seen before.

Her trip started in Borneo following a letter to the Rajah and Ranee of Sarawak, rulers of the province of Kuching and who played host to North upon her arrival. The trip was documented not only in North’s own autobiography, ‘Recollection of a Happy Life’, but in the Ranee’s, ‘Good Morning and Good Night’ published in 1934, the latter painted North on a somewhat flawed canvas; large-nosed, thin-lipped with a skimpy wardrobe, armed with her oils and brushes, evident of her one true passion. In her autobiography, she writes,

‘I had long dreamed of going to some tropical country to paint its peculiar vegetation on the spot in natural abundant luxuriance.’

And so she did.

In 1876 her focus shifted to one peculiar plant, and ours, the journey undertaken to find it. By the time North travelled to Borneo, her globetrotting ways had led to an impressive 800 paintings in her name, allowing her to capture the foliage, flowers and fruits of the pitinga in Jamaica and the flying possums of the gum trees in Australia. What came as a great surprise was her distaste for the local indigenous population; her criticism of The Dayaks was more aligned with the common European belief - they were savages. She found the traditional head-hunting practices of the indigenous tribes of the region quite disturbing, her opinions at odds with her well-travelled manner. The beauty and pride she found in capturing the unique biodiversity notably didn’t translate with the people.

Nymphaea stellata, South Africa. (© RBG Kew)

Her outlandish presence made for a rather unwelcoming reception for the Rajah; a powerful figure unused to being unchallenged. Well, at least about his Orchids. Short-tempered and a clash of personalities seemed to overpower reason in some instances - most notably, Ranee accounts, after which they’d eaten curry for dinner. One evening, North proposed to paint one of the Rajah's prized orchids and, after a sour disagreement regarding their pruning, led the Rajah to trample the delicate blooms into the earth. Comedic if not venturing slightly into the tyrannical, and as to what became of his character, we don’t know for sure.

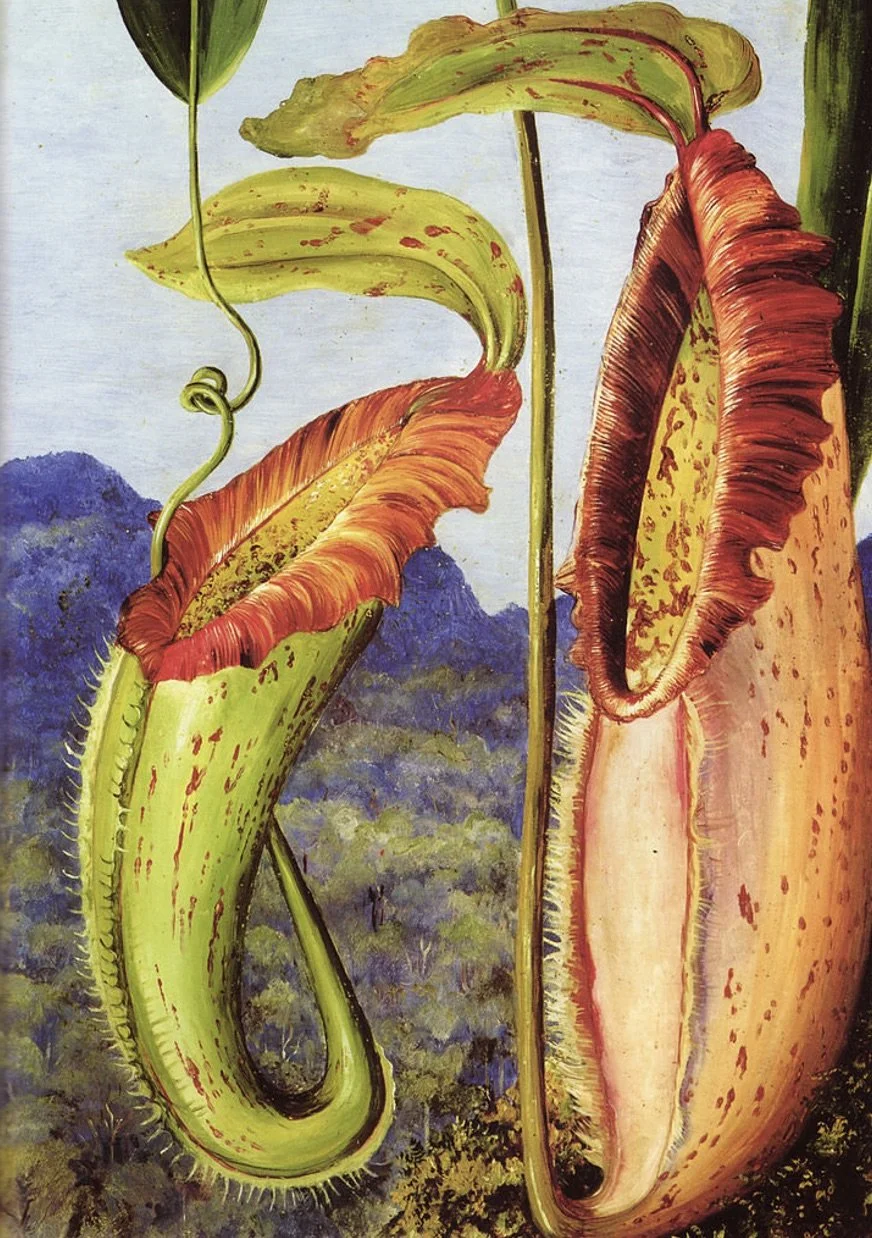

It was no doubt that North was an intrepid character, wasting no time going in search of the specimen unbeknownst to the scientific community. Her companion, Mr Herbert Everett, a knowledgeable guide, was said to have ‘traversed pathless forests amid snakes and leeches’ to find and deliver the plant to North. The specimen was unique in that they only grew on branches of trees about 1000 feet above the sea on the limestone mountains of the region. She painted a picture of the largest, describing the pitchers as ‘often over a foot long, and richly covered with crimson blotches.’ Whilst many eyes laid upon these unusual plants before European travellers came, she was undoubtedly the first to illustrate the species. An impressive feat, to say the least.

North, who offered a less congratulatory presence, painted her subjects surrounded by their unique ecology, unlike many of her colleagues who insisted on ferrying the specimens back to Europe. She preferred colour and depth, bringing a personality to every plant she drew, of course rebelling against the more anatomically accurate two-dimensional representations and I dare to say uninspiring prints of specimens one would typically see in a textbook.

Whilst her art paid an important contribution to botanical science, and one that shaped its future-it wasn’t entirely innocent either. Her travels brought her throughout the tropics and many parts of the British empire. Her Latin naming of the new species in line with the European classification system has contributed widely to the erasure of indigenous culture, shedding a language of a people who found the plant synonymous with her name now. In many ways, she was complicit in the spread of imperialist control. In one instance, the Ranee showed her a particularly beautiful flower for which North identified its Latin name in firm disregard of its true roots. Looking back against the unforgiving gaze of history, we memorialise the morbid, turn our backs on fallen empires and drown out the native tongue of the local tribesmen in favour of the maniacal scream of a bent-wing bat. With this, we should salute not just its more well-known epithet – the carnivorous pitcher plant (Nepenthes Northiana) but its native name, the Periuk Kera, as it is known in Malay.

Despite their differences in reason, the Ranee remarked upon North’s intelligence, friendship, and ability to open her eyes to the beauties of the world were amongst her fondest memories.

Pitcher plants of Borneo (c.1876 )

Perhaps she wasn’t the most well-liked woman or the most well-remembered. Still, she remains undeniably a trailblazer for which she well and truly marks her foundation in history.