Theatre Review: King Lear

King Lear

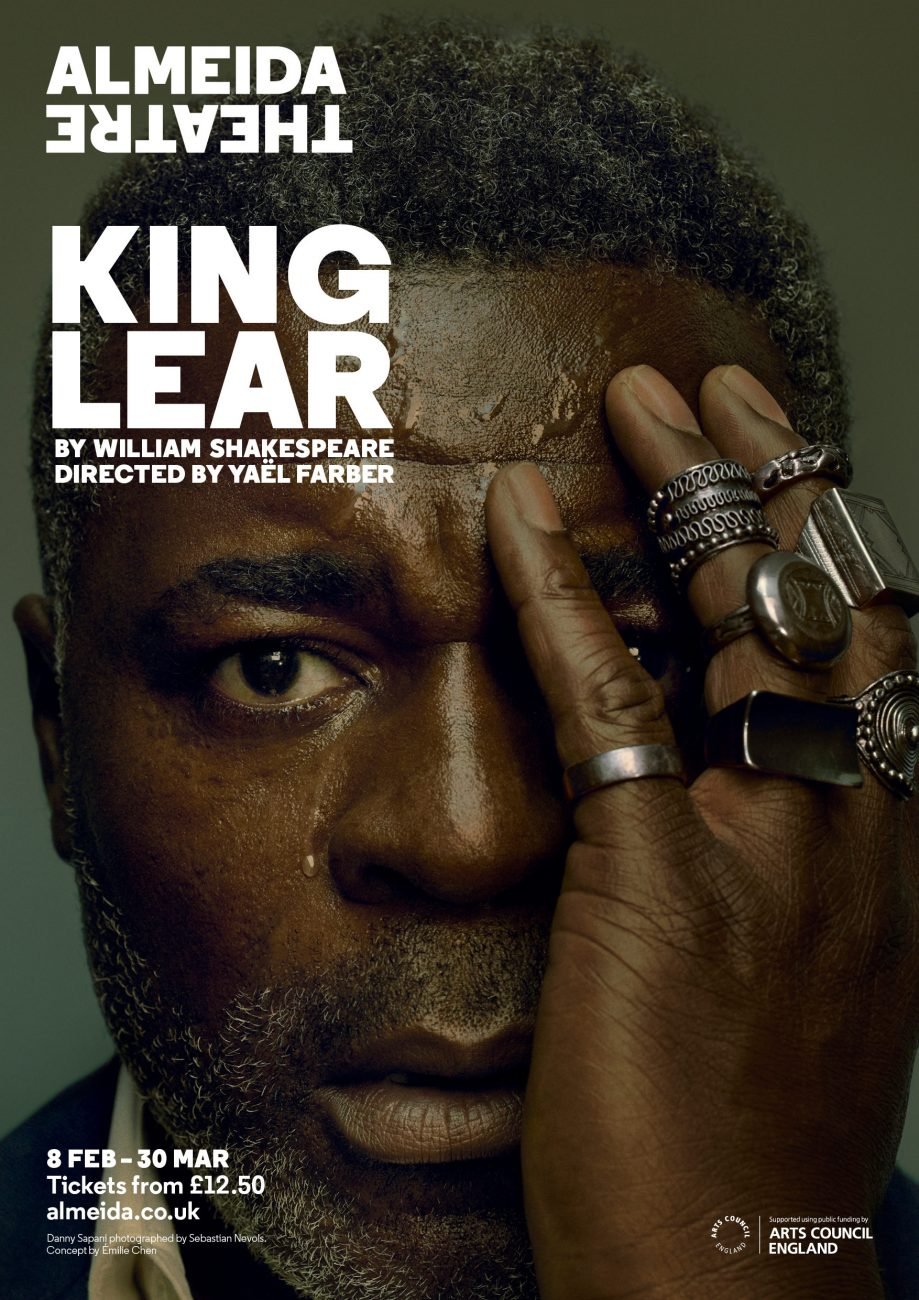

Almeida Theatre Production

8/2/24-30/3/24

Directed by Yaël Farber

Written by William Shakespeare

Review by Noor Zohdy

A silent, grey space surrounded by curtains of silver chains. A single silver globe. The chilling beauty of two violins (played by actors Oliver Cudbill and Steffan Rizzi) darkened among the audience. Moments later, a man with a whitening beard getting dressed. Then, spotlights, tight suits, and microphones that thunder. The Almeida Theatre production of King Lear was sweepingly spectacular to behold; chilling, forceful and inspired from its first moment.

One of the most compelling aspects of the play was its representation of the tragedy of sibling relationships. Edmund’s (Fra Fee) first embrace of Edgar (Matthew Tennyson) feels sincere; yet their conversation feels fraught, caught up in a web of Edmund’s desperate hatred of the prejudice and suspicion to which his life and identity has been made subject. An interesting aspect of the rendition was making Edmund Irish. With the modern historical associations, it made me realise, for the first time, that despite the fact that they are indeed brothers, English Edgar is an undeniable agent of the experiences of oppression felt by Edmund. This poignantly complicates their rivalry; and yet they are brothers, the play made me feel it undeniably. It caught me in the very same gulf Edmund himself perhaps feels. This keen, subtle portrayal of a lapse between Edmund and Edgar despite their connection gave their relationship a profound resonance I had never before appreciated. When Edmund says to his terrified brother, ‘I do serve you in this business’, sending him away to flee the wrath of their father, I could not but think he was somehow genuine ─ could there be something of Edmund trying to save his brother from the violence and cruelty that seems to become such an awful necessity? Thereafter, in the duel scene, Edgar’s return to this horrific world becomes a shocking, terrible moment in which the two brothers grapple as brothers; Edmund’s death happens in a split-second, Edgar hardly kills him ─ it has something of the inescapable, inexplicable tragedy of Cordelia’s death.

The most enduring image in my mind is at this moment. The stunning white lights illuminate Edmund (Fra Fee) and Edgar (Matthew Tennyson) caught in a fraught embrace as they recognise each other, while in a separate spotlight to their left, Goneril (Akiya Henry) desperately clutches her sister, Goneril (Faith Omole), who she has poisoned, before falling by her side, dying by suicide, holding her sister’s hand around her face. It brings together the keen, complex allyship felt of the sisters throughout. It was an utterly breath-stilling moment. The indescribable tragedy and loss of those mere seconds returned to my mind again and again as I thought about the play. In a world fraught by loss, destruction, and an ever-vanishing sense of self, these characters seek so tragically, so painfully to hold on to this vestige of themselves, their identities, and fragments of their love never fully realised in life. This wordless touch of truth and humanity made the play more real than I have ever before felt it to be. I felt for Edmund and Regan with all my heart.

Cordelia (Gloria Obianyo) and Lear (Danny Sapani) were beautifully done. In the opening scenes there is a stunning moment when Cordelia is desperately trying to convey to Lear the true nature of her speech; she is clutching his face and speaking with all her heart. Lear replies with the same gesture, yet somehow I felt his touch was cold. In his disaffected tone, he is already half-gone, words dwindle, and anything else feels impossible. Further, in the portrayal of children and parents, I felt a new poignancy in the relationship between Edgar (Matthew Tennyson) and the Earl of Gloucester (Michael Gould). The keen emotion of Edgar each time he said ‘give my thy hand’ to the Earl of Gloucester, made me appreciate the beautiful simplicity of that phrase and made me realise how it works as a refrain throughout. Amidst the fragmentary nature of their relationship, this simple form of touch is all they have. As every one of his identities, Edgar can be human nonetheless: still be a true voice to one who only hears disembodied sound. The words too made me feel his terrible pain at the impossible distance between him and his father despite their closeness; it brought out the spiralling impossibilities that shone across the play. Only four words, and yet they left me once again feeling a devastatingly complete sense of tragedy.

The Fool (Clarke Peters) was touching; he managed to create the presence of an archaic, lost soul, detached from reality, and yet keenly indivisible from it. He is ever-present, yet always tight-roping the liminal space of the mind. In one instance, the Fool vanishes off-stage as Lear looks restlessly about for him, then pauses with keen vulnerability to say, ‘let me not be mad’: the haunting, complex role of the Fool comes forth entirely anew. One of my absolute favourite moments was when Edgar was transforming his identity to Poor Tom. As he casts his clothes aside and streaks dark marks down his body, the Fool walks on stage as if by chance. He looks over at Edgar in curiosity. In the shadow of his spotlight he comes forward and as Edgar looks searchingly into the distance, the Fool lets fall white ash upon Edgar’s head, shining ghostly in the stark light. The Fool blows the last fragments from his fingertips where it billows hauntingly above Edgar’s head as the Fool vanishes into the darkness. It was a moment, caught in shadowy silence, so complete, so transfixing, I find words cannot do it justice.

The storm scene was visionary. I had a sense of Lear (Danny Sapani) out in the middle of the ocean caught in a wild tempest. Under icy blue shifting lights with his torn clothes, Lear seemed to stand on the edge of the world shouting out as the storm raged on thunderously. The haunting violinists (Oliver Cudbill and Steffan Rizzi) interwove their song with the chaos, rising now to magnificence and then dwindling to single, chilling chords. The Fool drifted beneath Lear’s feet like something airless caught in the wind. With the extreme lights, the magnificent power and force, it was a stunning portrayal of the world of extremity: the extremity of human suffering, feeling, the very limits of humanity itself. There was nothing beyond that stage ─ everything, absolutely everything, I felt convinced, was right there blazing forth.

A touching, inspired aspect of the performance was a song made out of the Fool’s (Clarke Peters) prophesy monologue; its final lines are sung by Cordelia (Gloria Obianyo). At the end of the play, all is lost and all the fallen darkened bodies lie on stage. Then, the violinists (Oliver Cudbill and Steffan Rizzi), fallen as if struck down, slowly rise. Heartrending music fills the stage as the Fool (Clarke Peters) appears on stage and walks among the destruction. He goes to Cordelia and gently pushes her head to rise. The globe that was centre stage at the beginning, returns, scorched black; flames suddenly break from it and Cordelia starts to sing. Slowly, everyone rises and fills the stage with ethereal choral echoes. Lear (Danny Sapani) vanishes in the shadows. In Cordelia’s final words, the play comes together as a delicate portrait of the magnitude of human suffering, human resilience, and the sweeping, tempestuous reign of tragedy. In the brilliant lights and rising song, the play exists all at once and yet not at all. I felt cast backwards somehow. The choral music and the risen bodies transform the stage with a sudden unreality. Under the shimmering lights, flushing the stage gold, every actor seemed ever so slightly cast in stone.

This prophecy Merlin shall make, for I live before his time.